Similar

National currency / JS Conway. - Public domain dedication image

Summary

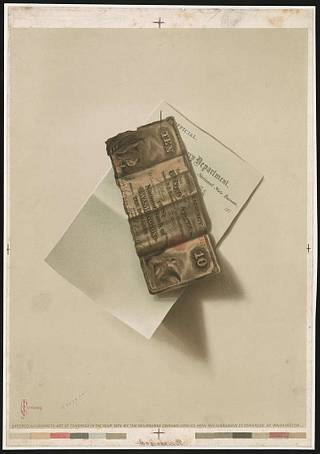

Print shows a trompe-l'oeil presentation of a U.S. $10 national currency issued by the "National Bank of Washington" pinned to a notice from the "[Treas]ury Department, National Note Bureau".

C3279 U.S. Copyright Office.

Entered according to act of Congress in the year 1872 by Milwaukee Chromo Lith. Co. with the Librarian of Congress at Washington.

Copyright number inscribed in pencil on lower left corner.

Includes print registration marks on all sides and a color bar, indicating 12 stones, across the bottom.

Money in the colonies was denominated in pounds, shillings, and pence. The value varied from colony to colony; a Massachusetts pound, for example, was not equivalent to a Pennsylvania pound. All colonial pounds were of less value than the British pound sterling. The prevalence of the Spanish dollar coin in the colonies led to the money of the United States being denominated in dollars rather than pounds. Due to almost no money supply from Britain to colonies, colonies had to issue their own paper money to serve as an exchange. In 1690, the Province of Massachusetts Bay created "the first authorized paper money to pay for a military expedition during King William's War. Other colonies followed the example by issuing their own paper currency in subsequent military conflicts, to pay debts. The paper bills issued by the colonies were known as "bills of credit." Bills of credit were usually fiat money: they could not be exchanged for a fixed amount of gold or silver coins upon demand. The governments would then retire the currency by accepting the bills for payment of taxes. When colonial governments issued too many bills of credit or failed to tax them out of circulation, inflation resulted. This happened especially in New England and the southern colonies, which, unlike the Middle Colonies, were frequently at war. Pennsylvania, however, was not issuing too much currency and it remains a prime example in history as a successful government-managed monetary system. Pennsylvania's paper currency, secured by land, was said to have generally maintained its value against gold from 1723 until the Revolution broke out in 1775. This depreciation of colonial currency was harmful to creditors in Great Britain. The British Parliament passed several Currency Acts to regulate the paper money issued by the colonies. The Currency Act of 1751 restricted the emission of paper money in New England. It allowed the existing bills to be used as legal tender for public debts (i.e. paying taxes), but disallowed their use for private debts (e.g. for paying merchants). Currency Acts of 1751 and of 1764 created tension between the colonies and the mother country and were a contributing factor in the coming of the American Revolution. When the American Revolutionary War began in 1775, all of the rebel colonies, soon to be independent states, issued paper money to pay for military expenses.

Alois Senefelder, the inventor of lithography, introduced the subject of colored lithography in 1818. Printers in other countries, such as France and England, were also started producing color prints. The first American chromolithograph—a portrait of Reverend F. W. P. Greenwood—was created by William Sharp in 1840. Chromolithographs became so popular in American culture that the era has been labeled as "chromo civilization". During the Victorian times, chromolithographs populated children's and fine arts publications, as well as advertising art, in trade cards, labels, and posters. They were also used for advertisements, popular prints, and medical or scientific books.

Tags

Date

Contributors

Source

Copyright info